How Well Do You Know Your Chiles?

Types of Chile Peppers

There is some debate about the exact number of types of chile peppers, but experts all agree that the number reaches into the thousands. Peppers worldwide come in various shapes, sizes, and flavors. You can find large peppers or small ones, or ones that are sweet and mild or spicy hot.

Learning about chile peppers can take time and effort and can occasionally seem complicated, but it’s worth the effort to gain some understanding of these delicious pods. We can help you start to make sense of what there is to know about chiles.

The Spices, Inc. team has been sourcing, processing, and selling chiles worldwide for more than 10 years. Our chiles are sought after by restaurants, manufacturing facilities, microbreweries, and home cooks.

We have expertise regarding chiles, and want to pass that along. We can help you figure out what chiles you want and need, outline the kinds of chiles you’ll find when you shop, and even give you a glimpse into their fascinating history.

How Many Peppers Are There?

Some sources claim approximately 4,000 types of peppers are found worldwide. Other sources estimate there can be as many as 50,000 varieties, though the more significant number approximates the number of undomesticated wild peppers1.

Table of Contents

How Many Species of Capsicum Are There?

What Are the Five Domesticated Capsicums?

Capsicum Origin

Capsicums, the botanical genus to which chile peppers belong, initially emerged in South America. Food historians and archaeologists point to eastern Bolivia as the birthplace of the chile pepper, up in the eastern mountains. Wild chiles first appeared circa 7500 BC; they were fully domesticated in Mexico in 4100 BC.

Capsicums, the botanical genus to which chile peppers belong, initially emerged in South America. Food historians and archaeologists point to eastern Bolivia as the birthplace of the chile pepper, up in the eastern mountains. Wild chiles first appeared circa 7500 BC; they were fully domesticated in Mexico in 4100 BC.

The Domestication of Chiles

In all probability, Capsicum annuum, the most common chile species available today, was the first pepper to be domesticated. It’s also likely that it was a relative of the wild bird pepper, C. annuum v. glabriusculum, and you can find that pepper’s ancestor is still thriving in the Chiltepin pepper2.

A large, coordinated study examined four types of evidence—plant genetics, archaeobotanical information, species distribution analysis, and paleobiolinguistics3. While the genetic studies seemed to point most strongly toward northern Mexico as the area in which peppers were first domesticated, all four lines of evidence—genetics included—pointed firmly to the central-eastern part of the country as the original site of domestication, stretching from the mountains of Puebla to tropical southeastern Veracruz.

While wind and water helped move some seeds away from their emergence point, birds are primarily credited with transporting chiles over large distances. They don’t have receptors for capsaicin in their mouths, so they can eat the chiles without enduring the heat. Birds would eat chile peppers regardless of their spice level and transport seeds in their bellies during migration.

How Many Species of Capsicum Are There?

There are currently as many as 27 distinct species of capsicums, which is subject to discussion considering the fluid way chile peppers propagate and hybridize.

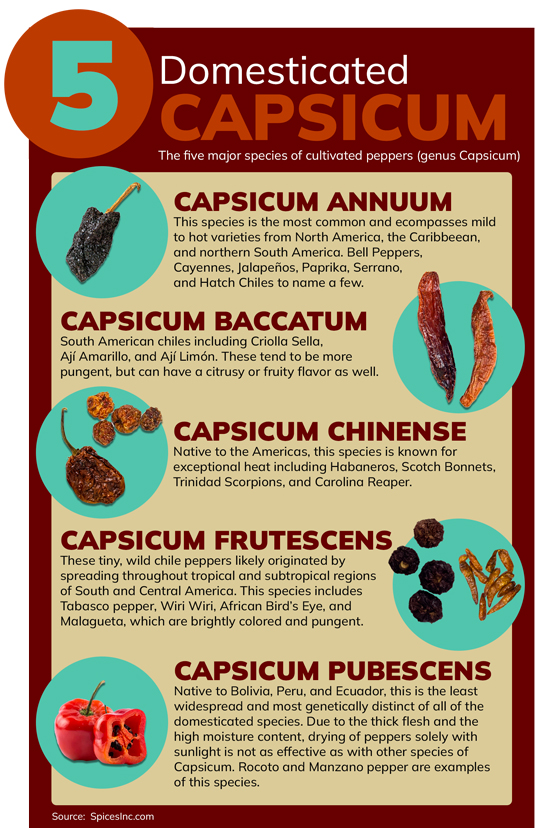

Regardless of how many pepper species there are, five of that number are domesticated, which means they are specifically grown and nurtured for human use. Humans may use other wild species of chile, but they are not necessarily farmed for our consumption.

What Are the Five Domesticated Capsicums?

The five domesticated capsicum species are Capsicum annuum, Capsicum baccatum, Capsicum chinense, Capsicum frutescens, and Capsicum pubescens.

Capsicum Annuum

Capsicum annuum is the first domesticated pepper species with the most significant number of varietals in cultivation. They encompass an enormous range of characteristics; they can be large and mild, or small and spicy, with thick or thin flesh and fruity, deep, or clean flavors.

In warmer climates, these pepper plants can live through several growing seasons, but they are sensitive to frost and have to be replanted yearly in cold-winter regions, giving them their “annual” name.

| Capsicum annuum | Scoville Heat Units (SHU) |

| Aji Paprika | 100-500 SHU |

| Anaheim | 500-1,000 SHU |

| Ancho | 1,000-1,500 SHU |

| Byadgi | 15,000-25,000 SHU |

| Calabrian | 5,000-25,000 SHU |

| Cascabel | 1,500-2,500 SHU |

| Chiltepin | 100,000-250,000 SHU |

| Chipotle Meco | 2,500-10,000 SHU |

| Chipotle Morita | 2,500-10,000 SHU |

| Choricero | 175-300 SHU |

| Costeno Rojo | 5,000-15,000 SHU |

| de Arbol | 15,000-30,000 SHU |

| Guajillo | 2,500-5,000 SHU |

| Guntur Sannam | 25,000-30,000 SHU |

| Hatch New Mexico | 800-1,400 SHU |

| Japones | 15,000-30,000 SHU |

| Mulato | 1,000-1,500 SHU |

| Nora | 500 SHU |

| Pasilla de Oaxaca | 15,000-20,000 SHU |

| Pasilla Negro | 1,000-1,500 SHU |

| Pequin | 30,000-60,000 SHU |

| Puya | 5,000-10,000 SHU |

| Smoked Red Serrano | 8,000-18,000 SHU |

| Thai Bird | 70,000-130,000 SHU |

| Tien Tsin | 10,000-60,000 SHU |

Capsicum Baccatum

The Capsicum baccatum species is primarily comprised of chiles from South America. These peppers tend to deliver pungent heat and fruity flavor. They are pretty thin-skinned. When the peppers start to develop, they hang off their plant, as a berry would. Baccatum means “berry-like” and can refer to their physical resemblance to a berry and fruity flavor.

| Capsicum baccatum | Scoville Heat Units (SHU) |

| Aji Amarillo | 30,000-50,000 SHU |

| Aji Panca | 500-1,500 SHU |

| Criolla Sella | 20,000-30,000 SHU |

Capsicum Chinense

Capsicum chinense peppers are extremely hot and spicy but have delicate flavors that underlie the heat. These chiles are usually small, and the fruits develop into unique and interesting shapes—round like a lantern, squashed flat like a Scottish cap, or with a lethal-looking hooked tail.

This pepper species carries a misleading name. Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin is the Dutch botanist who named the species. He gave it this name because he mistakenly believed this pepper developed in China since it was a regular feature in Chinese cuisine.

This pepper species first emerged in the Americas; when European traders brought this chile to Asia, its fiery bite was readily embraced by local cooks.

| Capsicum chinense | Scoville Heat Units (SHU) |

| Ghost | 1,000,000 SHU |

| Habanero | 150,000-325,000 SHU |

| Scorpion | 500,000-1,400,000 SHU |

| Scotch Bonnet | 200,000-300,000 SHU |

Capsicum Frutescens

The Capsicum frutescens species grow on bushy plants throughout South and Central America. They may survive a few growing seasons if weather permits. The fruits on these plants tend to be small and potent, with high heat levels and punchy flavors.

It is thought to be an ancestral strain that led to the emergence of Capsicum chinense. Because these peppers are small and colorful, this plant is often grown ornamentally.

| Capsicum frutescens | Scoville Heat Units (SHU) |

| African Bird’s Eye | 100,000-225,000 SHU |

| Malagueta | 120,000-160,000 SHU |

| Wiri Wiri | 60,000-80,000 SHU |

Capsicum Pubescens

Capsicum pubescens is a unique pepper family. They are the only pepper family that tolerates colder weather; it will wither in the heat, though a hard frost will also kill this plant. The seeds of the pubescens fruits are black instead of white or cream-colored.

It was named for its odd, hairy leaves and stems. Peppers take nine months to mature on their plant, and the flesh is very thick. This makes a fresh pubescens excellent for stuffing but not amenable to drying without dehydrators.

This pepper enjoys much less diversity than the other pepper species. It has the fewest amount of varietals than the other species. Capsicum pubescens are mainly found in Central and South America and a few areas of Indonesia, but not beyond.

| Capsicum frutescens | Scoville Heat Units (SHU) |

| Rocoto*** | 30,000-80,000 SHU |

| ***Rocoto are only available for sale as chile flakes |

What Do Chile Peppers Look Like

Chile peppers come in various shapes, sizes, and colors. These various chile pod types don’t have a singular look.

Some peppers are small, round, and look like red berries. Some are wide and flat and look like the head of a shovel. The iconic shape has them longer than they are wide and tapering to a point, with or without a curve in the middle.

They can come in fanciful shapes; the Scotch Bonnet got its name thanks to a passing resemblance to a tam o’ shanter, the traditional flat cap worn by Scotsmen.

The critical thing to remember about the appearance of chile is that larger chiles tend to be sweeter and milder, while smaller chiles tend to carry a lot of heat.

Are Chile Peppers Hot?

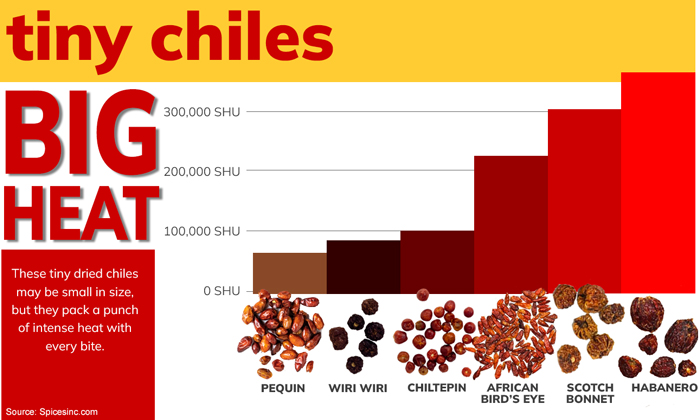

There is a common misperception that chile peppers are all hot, but that’s not necessarily the case. Chile peppers are famous for their heat, which can be searing. A chile’s heat is measured in Scoville Heat Units (SHU), named for the pharmacist who devised the method to test the chiles.

Most of us are familiar with the sting of a jalapeno, with a heat range of 2,500-8,000 SHU. This is considered to be a medium heat chile. On the high end, peppers like the Scorpion chile are about 280—that’s not a typo—times hotter than a jalapeno.

However, there are incredibly mild chiles. The Nora is sweet and fruity, with a heat level of just 500 Scoville Heat Units (SHU). The Ancho pepper, with a flavor like raisins with rich chocolate notes, contains just 1,000-1,500 SHU. And let’s not forget that sweet bell pepper is a chile pepper—this member of the Capsicum annuum species measures at 0 SHU. While chiles can be hot, it is not a categorically defining characteristic.

The Flavors of Chiles

The Flavors of Chiles

We’ve identified 40 flavors that chile peppers can express. Peppers can deliver a surprising amount of rich and varied flavors, even in the same fruit. A pepper like a Guajillo, SHU 2,500-5,000, is smoky, sweet, astringent, piney, and tastes like tart berries.

Often the flavors in peppers are more recognizable in mild chiles. When you eat a spicy pepper, it’s easy for your mouth to become overwhelmed by the heat, to the point that it has difficulty distinguishing flavors. Hot peppers are often bred for their heat and sacrifice flavor in favor of more heat.

However, a Habanero, which we consider a “crazy hot” pepper, has beautiful tropical flavors like papaya and coconut layered below the heat. If you can get past the heat through processes like deveining or deseeding, you’ll discover a wealth of rich and fruity flavors.

Chiles vs. Peppers

While the terms “chile” and “pepper” have become interchangeable in the US, at one point in history, they meant very different things.

Chile is derived from the word chīlli, the Nahuatl term used by the Aztecs. It means “hot pepper”, and refers specifically to members of the Capsicum genus that they would eat and sell in the markets of Mexico. Spanish conquistadores adapted the word chīlli into their language as chile and applied that to the very same hot peppers that we still call chiles today.

Pepper, at one point, referred only to Piper nigrum, black pepper, or its cousin Piper longum, long pepper. The naming of this spice gets a little mixed up thanks to Christopher Columbus. Columbus launched his journey to find a western sea route to India and the surrounding regions in an attempt to gain control of some of the spice trade.

Columbus and his sailors did not know about the American continents or the Pacific Ocean, so they only thought they had an Atlantic Ocean crossing to contend with. When Columbus landed in the Bahamas, he didn’t realize how far he was from his intended destination and thought he had discovered a new passage to India.

When he was given a spicy chile to try, the bite of the chile reminded him of the spiciness of black pepper. It was this name he erroneously gave to chiles when he brought them back to Europe and presented them at the Spanish court.

People in the US continued to use both names for these fruits; initially, “chile” was the preferred term in the American southwest, while “pepper” was used in the rest of the country. With the modern American embrace of Mexican and other cuisines, like Thai, which use spicy chiles, there’s been an increased understanding of the origins of chiles. This has brought on a willingness to call them by the original name used by the Aztecs so long ago.

Chile peppers take some time to get to know, but they can bring spicy fire and loads of nuanced flavor to a dish. They’ve become famous worldwide because they contain so many robust and delicious culinary characteristics in one ingredient. We’re confident that once you get used to working with their flavors and heat levels, they’ll become an indispensable part of your kitchen, too.